6 July 2022

Over recent years, several record-breaking sales have established nonfungible tokens (NFTs) as the new black in the world of art. These secure, authenticated digital certificates allow the acquisition of virtual art, which means new income opportunities for artists and a greater interest in digital art among museums. But are we really witnessing a revolution, or a speculative bubble about to burst?

Catherine Hickley

Journalist and author based in Berlin

Most people outside the world of blockchain and crypto currencies probably first became aware of nonfungible tokens, or NFTs, in March 2021, when the auction house Christie’s sold 'Everydays – The First 5,000 Days', a collage by an artist known as Beeple (his real name is Mike Winkelmann), for the eye-popping figure of US$69 million.

The sale made Beeple – who had been unknown in the traditional art world – one of the most expensive living artists. It prompted baffled news headlines and unleashed a speculative frenzy on NFT platforms.

That gold rush still continues, despite the successive crashes that have affected the crypto currency market. But regardless of the market, NFTs have already had an impact on the course of art history. Many experts in digital art see the colossal price-tag for Beeple’s work (which no NFT sale has since even come close to) as an extension of developments that can be traced back to the middle of the last century.

Turning point for digital art

“We were all taken by surprise by these high prices for NFTs, but we probably shouldn’t have been”, said Alfred Weidinger, the director of the Oberösterreiches Landesmuseum in Linz, in Austria. “Digital art is nothing new. There has been a continual development, and even NFTs have been around for some time.”

One of the museums Weidinger oversees, the Francisco Carolinum in Linz, is celebrating the 95th birthday of Herbert W. Franke, a trailblazer of computer art, with an exhibition – and an NFT “drop” (sale) to benefit his foundation. This Austrian precursor, who is also a science fiction writer and a physicist, produced abstract algorithmic art on a computer as early as the 1960s.

It is important to understand that NFTs are not, in themselves, artworks. An NFT is simply a token, or a certificate, with a unique code secured by a blockchain protocol – a data storage and transmission technology designed to be transparent and secure at the same time. The most commonly used protocol is Ethereum. An NFT can be attached to any form of information: a deed of home ownership, a ticket for a concert, an internet meme, or a photo of your cat. Or even a social media post – days after the Beeple sale, crypto entrepreneur Sina Estavi paid US$2.9 million for an NFT of Twitter chief executive Jack Dorsey’s first tweet (Estavi tried to resell it for a vast profit a year later, and failed: the highest bid was US$6,800).

Unique objects for collectors

The application of NFTs to the art world, though, has stirred the most interest. From an artist’s point of view, tokenization is a way to turn a digital artwork, which is otherwise infinitely replicable, into a unique object that as such, can be sold and collected. This has already had far-reaching consequences, opening a world of new opportunities for artists working in the digital field.

tokenization is a way to turn a digital artwork into a unique object

“NFTs are an amazing tool for artists”, said Dirk Boll, the President of Christie’s Auction House in Europe and the Middle East. He likens the advent of NFT technology to the introduction of home glass-blowing equipment in the 1960s. “There was a huge release of creativity in glass art”, Boll said. “This is a comparable moment for digital art.”

Quantum, produced in 2014 by American artist Kevin McCoy, is considered the very first NFT. The project was developed in collaboration with the technologist Anil Dash and Rhizome, an organization affiliated with the New Museum for Contemporary Art in New York. Among the earliest collectible works are CryptoPunks, a set of 10,000 pixelated characters created in 2017 by Matt Hall and John Watkinson.

Established digital artists such as Refik Anadol, Kevin Abosch and Nancy Baker Cahill have embraced NFT technology. With his Rocket Factory, the space-focused American artist Tom Sachs has invited collectors to purchase an NFT of a part of a digital rocket. A physical rocket will be launched simultaneously: if it is recovered, the owner of the NFT will also receive the real thing.

Digital natives rush in

NFTs have opened the art world to new audiences. The generation of digital natives who are buying them have a different demographic background from collectors who visit auction houses and galleries. Many enter the NFT world via computer games and crypto currencies – hence the huge value placed on the work by Beeple, an artist with a background in animation and graphic design who often satirizes the tech world and peppers his art with references to popular internet culture.

The market for NFTs is still not for the fainthearted, fuelled largely, as Boll put it, “by people with crypto money who don’t know what to do with it”. It is “radically more rife with speculation” than the analog market, wrote Marc Spiegler, the global director of Art Basel, an international art fair organized annually in Basel, Switzerland, in his foreword to the fair’s 2022 Art Market Report. The exceptional growth in value in 2021 was “driven by short-term trading,” he said, adding that “on average, art NFTs are owned for just over a month before being resold”.

The NFT market is more rife with speculation than the analog market

Marc Spiegler (global director of Art Basel)

The total market value of NFTs in 2021 was almost US$18 billion, according to data from the website nonfungible.com. Of that, US$2.6 billion was related to art. In the first quarter of this year, the volume of trades dropped slightly. A big test faced the market in May 2022, when more than US$300 billion was wiped out in three days as a result of a crypto-currency crash.

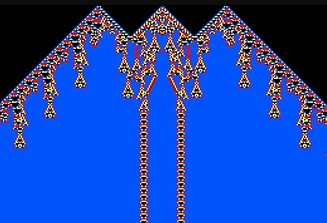

Detail from Everydays: The First 5,000 Days consists of 5,000 digital drawings created by American artist Beeple at a rate of one per day for the purpose of improving his drawing and graphic skills. The certificate of ownership (NFT) of this collage was sold for US$69 million in 2021.

© Mundissima / Shutterstock

Moment of truth

That may, in turn, cause the market to mature, said Boll. “There will be a big moment of truth”, he said days before the crash. “People will understand that there are a few interesting pieces of art as NFTs and a gazillion that are not.”

Christie’s and Sotheby’s were quick to enter the NFT market. A few art galleries have followed – for instance, in August last year the König Galerie in Berlin launched MISA, which it described as “the first art world NFT platform”.

But there are plenty of obstacles for conventional art market players that have a duty to conduct due diligence. The owner of an NFT, unlike the owner of a physical artwork, does not have possession of it – instead it is located on a digital platform over which he or she has no control. What happens if the platform goes bankrupt? While the legal framework races to catch up with technology, there is much about the market that remains risky.

One of the biggest drawbacks is the carbon footprint of NFTs – estimates for carbon emissions caused by an NFT sale on the Ethereum blockchain calculate them at about the same as those caused by a month of electricity use by a person living in the EU. More sustainable technology, however, is on the way, and some blockchains are already much more energy efficient. NFT advocates point out that the traditional art market is not more environmentally friendly, given the flights to trade fairs, exhibitions and biennials around the world, and the shipments of art from one continent to another.

Museums join the action

Museums also jumped on the NFT bandwagon, selling tokens of classic works to raise money in the cash-strapped pandemic-lockdown era. The Uffizi in Florence, for instance, sold an NFT of Michelangelo’s Doni Tondo last year for ˆ140,000. But as Weidinger pointed out, this is not selling art. He likened such tokens to “fridge magnets”.

Boll also described them as very expensive museum shop gadgets. “Museums are taking advantage of a certain window that will close, because people will realize it is not really interesting”, he said. “They are striking while the iron is hot.”

That window may already be closing: Vienna’s Belvedere offered 10,000 NFTs featuring fragments of Gustav Klimt’s Kiss on Valentine’s Day this year. Less than a quarter had been sold by early May, according to local press reports. Those trading in the secondary market were priced lower than the initial price-tag of ˆ1850.

Few museums have purchased NFTs of digital art for their own collections, Weidinger said. However, his museum is the only one in Austria to have acquired them. Another notable exception is the ZKM (Centre for Art and Media) in Karlsruhe, which purchased NFTs back in 2017, four years before the Beeple sale, and is now showing them in an exhibition called “Crypto Art: It’s Not About Money”.

Yet it was money - in vast quantities - that first brought NFTs to the attention of the general public. The Beeple sale, Weidinger said, served as a wake-up call, meaning that finally “museums are catching up and doing their homework on digital art”.

Cellular Automata (1992-1998) by Austrian artist Herbert W. Franke, one of the pioneers of computer art, as well as a science fiction writer and physicist.

© Herbert W. Franke / Archive art meets science

Original article

Permanent link: http://en.unesco.kz/art-market-goes-crypto-with-nfts